Ample Reserves Framework Primer: TBL Weekly #159

Dear Readers,

This week, we will take a short break from hashing out TBL Liquidity Indicator performances to create an educational piece on monetary policy dynamics—specifically, today’s ample reserves framework that the Fed uses. We partly addressed this in our latest Mean Median Mode report, but we will go into more detail today.

You know the story of bitcoin’s market cycles: euphoric blow-offs, brutal crashes. Maybe not anymore. The Bitcoin _Checkpoint takes a deep look at how the 2023–2025 cycle has rewritten market structure—and why these changes could be permanent.

Inside you’ll find analysis of record-low volatility, ETF flows absorbing billions monthly, and why long-term holders remain in control with $1.3T in unrealized profit. Plus, download now for automatic access to the event where James Check took a deep dive into the report himself.

We are also happy to announce our newest sponsor this month: Arch Lending!

At TBL, we help you decode Bitcoin’s macro trends and give clear market signals—holding Bitcoin is just the beginning. Arch lets you borrow against your Bitcoin—unlock cash without selling:

Instantly access a Bitcoin-backed line of credit

Borrow from just $5k for up to 2 years

No rehypothecation. Ever.

Insured custody at Anchorage Digital

Stay long, stay liquid.

Use code “Nik” for 0.5% off interest rate for 2 years.

Our videos are on major podcast platforms—take us with you on the go!

Apple Podcasts Spotify Fountain

Keep up with The Bitcoin Layer by following our social media!

YouTube X LinkedIn Instagram TikTok

The Fed’s prior framework

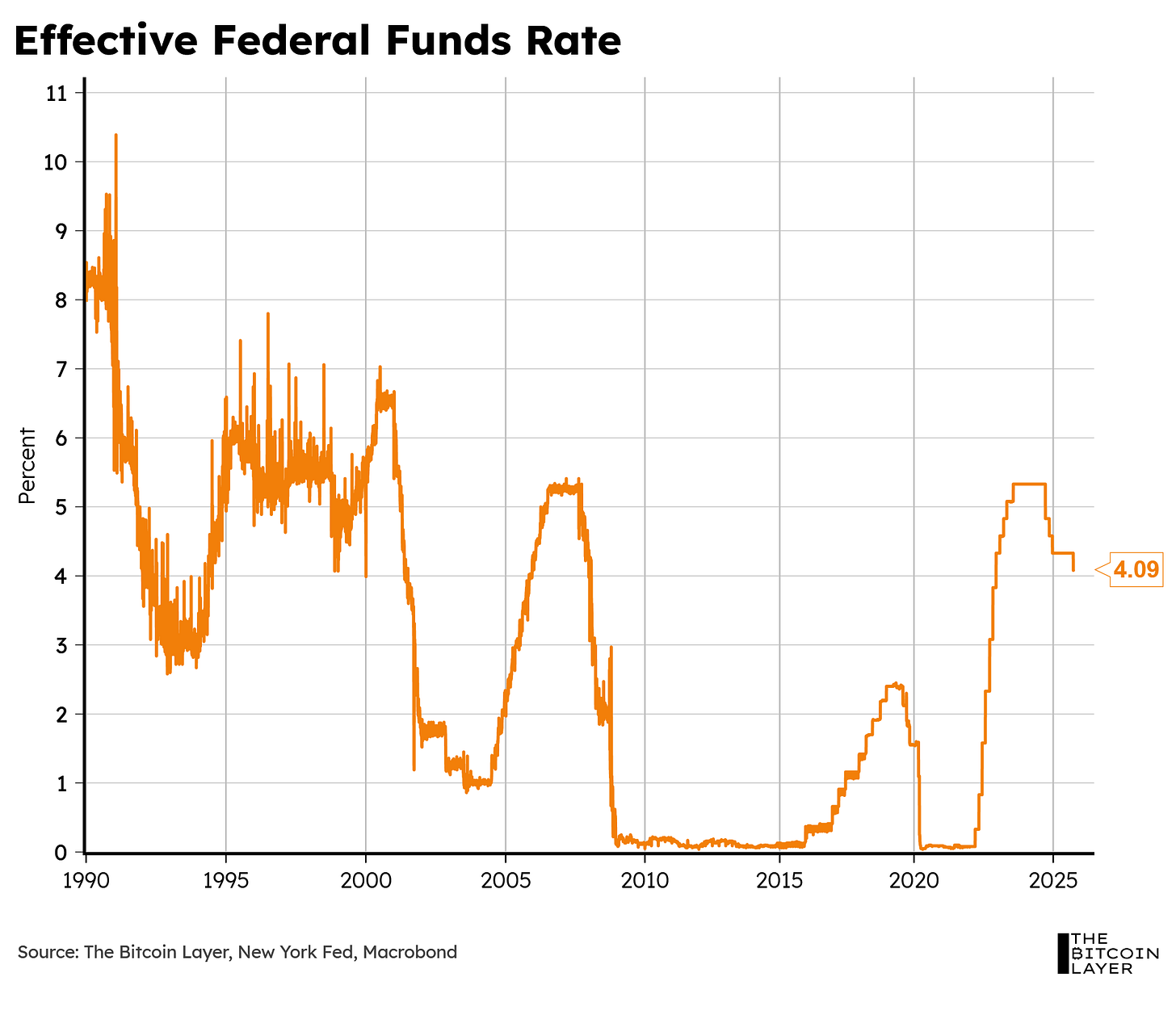

Since the 90s, we’ve all become accustomed to the Fed openly communicating its stance on monetary policy, setting a variety of operating targets over time. The point we intend to highlight in this article is the transformation of how the Fed employs such operating targets.

The Fed Funds market consists of unsecured loans between banks and financial institutions that are part of the Federal Reserve’s system. It is called “Fed Funds” rate because the rate is just the average rate on overnight loans in the Fed Funds market, or more specifically, loans for Federal Funds themselves, which is a fancy way of describing reserve balances held by banks at the Federal Reserve:

In the 90s, the Fed Funds market was crucial to anyone’s understanding of money market conditions. Back then, we lived in an era where the Fed primarily used its control over reserves as a means to apply (or remove) pressure on money market interest rates. Put another way, they set their policy rates by altering reserves in the system. Alan Greenspan’s communication of the Fed’s target rate showcases this perfectly. In the first-ever post-FOMC release, issued in 1994, the Fed addressed an increase in interest rates as follows:

“Chairman Alan Greenspan announced today that the Federal Open Market Committee decided to increase slightly the degree of pressure on reserve positions. The action is expected to be associated with a small increase in short-term money market interest rates.”

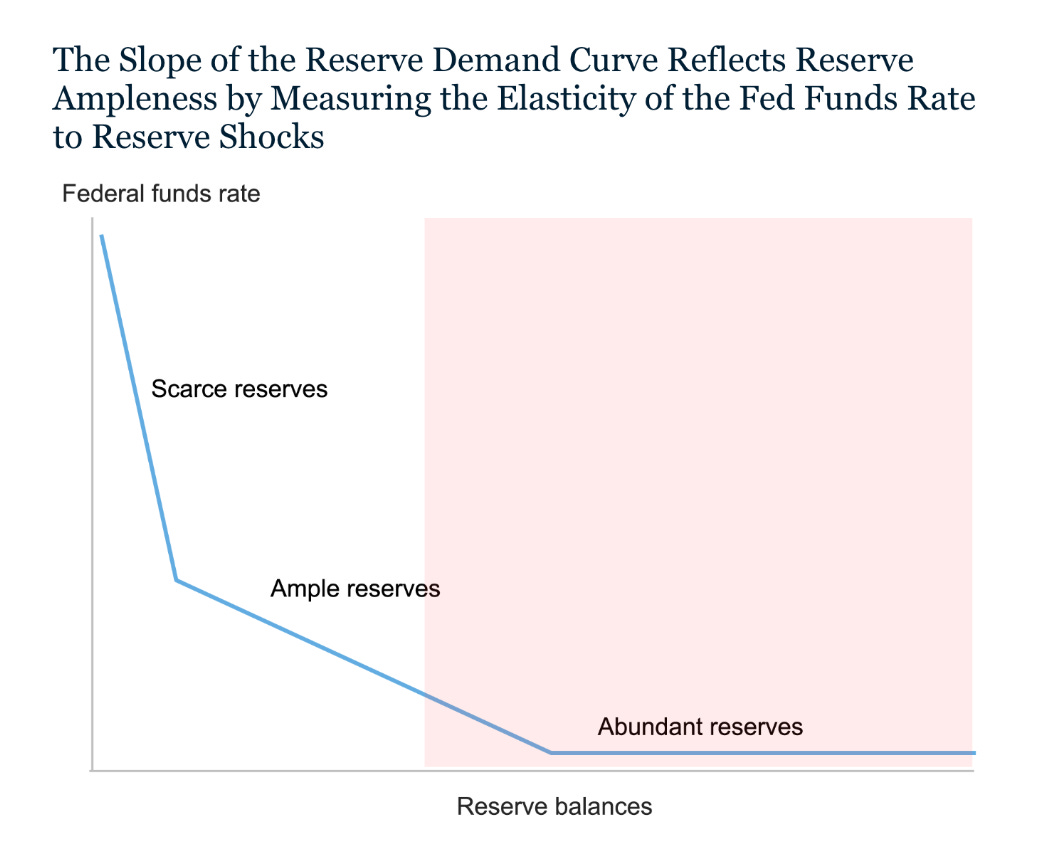

This necessarily meant that short-term interest rates were highly sensitive to reserves in the system, known in economics as the elasticity of the Federal Funds rate to changes in the supply of reserves.

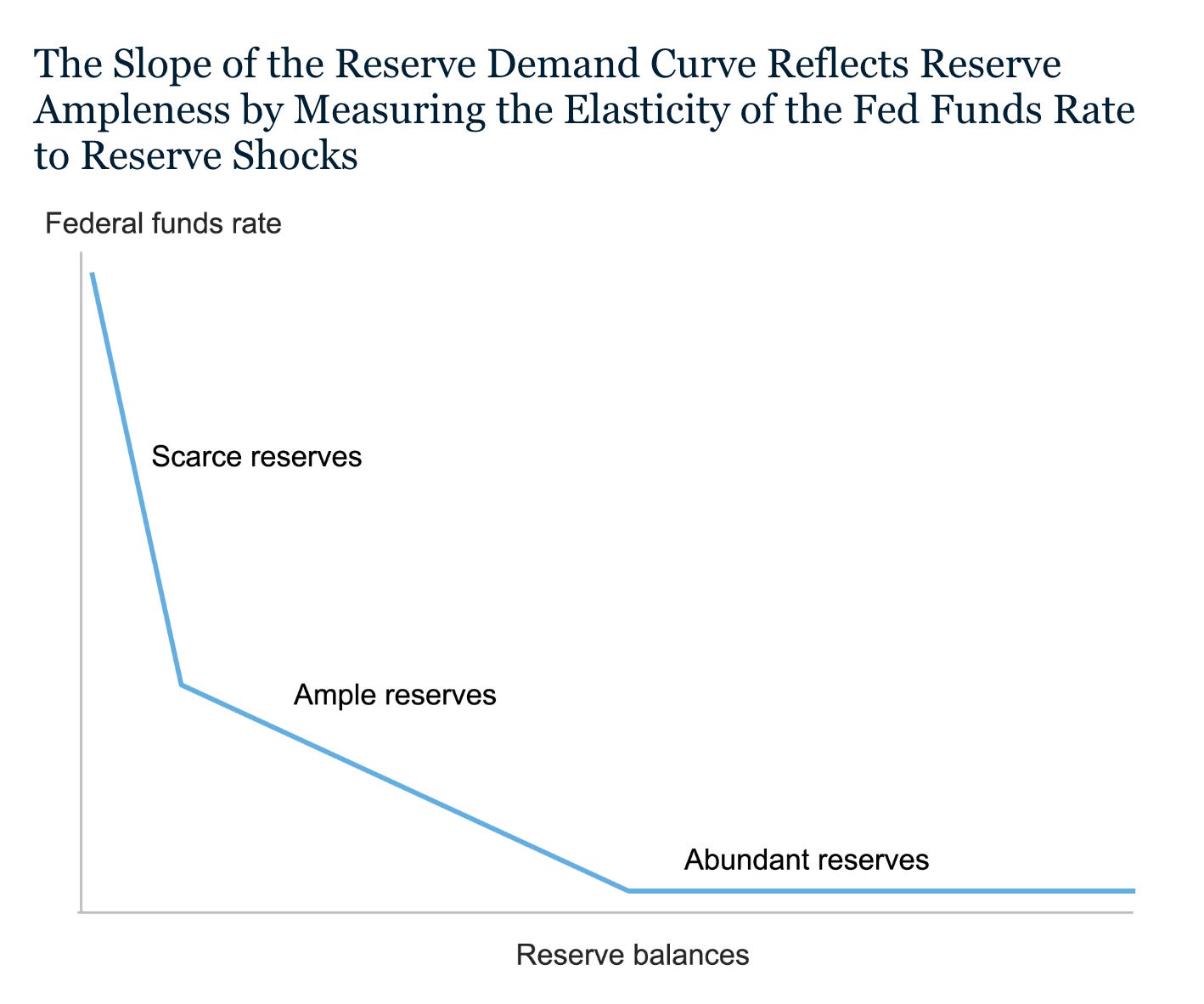

When reserves are scarce, changes in reserve balances lead to large changes in the Fed Funds rate, and when reserves are abundant, changes in reserve balances lead to little or no changes in the Fed Funds rate. Here’s a chart showing the Fed Funds rate as a function of reserve balances (this is what’s known as the ‘reserve demand curve’):

Notice how, in scarce reserve periods, the slope of this demand curve is very negative, while in abundant reserve periods, the slope is nearly flat (or zero)—this is important to remember as you keep reading this article.

So, building off of Alan Greenspan’s comments above, before the Great Financial Crisis (GFC), if the Fed wanted to lower interest rates from, say, 7% to 6%, they would go into the market and buy T-Bills with cash. T-Bill sellers would then take that cash and deposit it into banks. This would:

Increase the money supply in the system (lowering the price of money—read lowering interest rates).

Decrease yields on T-Bills, causing more downward pressure on short-term rates.

In other words, you could say that, back then, the Fed found itself closer to the ‘scarce reserves’ part of the reserve demand curve:

But markets have changed drastically since then, when banks relied on each other for short-term liquidity, without the presence of collateral.

The GFC transformation

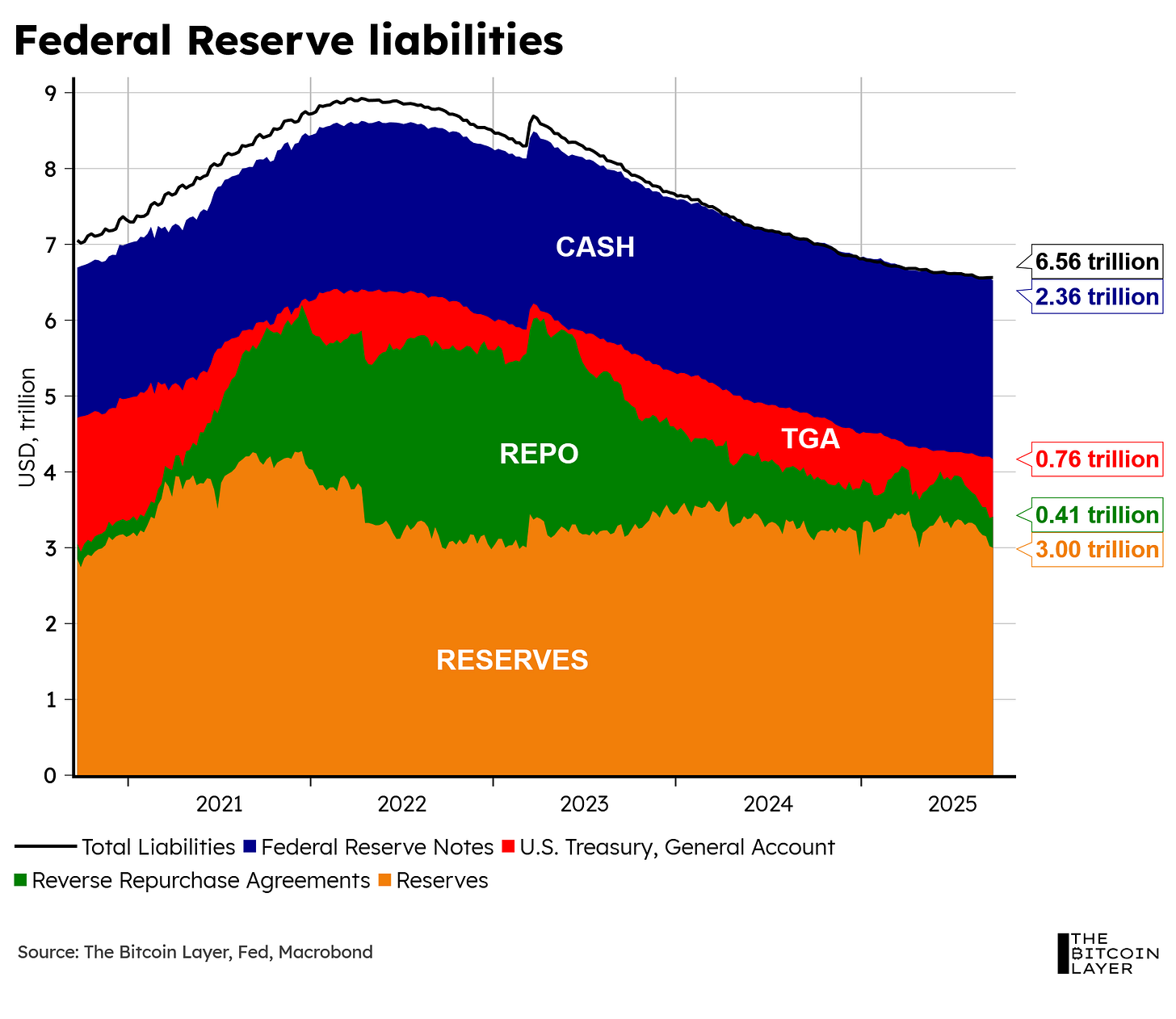

Part of the Fed’s role to the American public is to use its balance sheet to supply money (in the form of liabilities). The Fed’s balance sheet consists of three main liabilities:

Currency (Federal Reserve Notes)

Treasury General Account

Reserves

(Reverse Repo - more on this later)

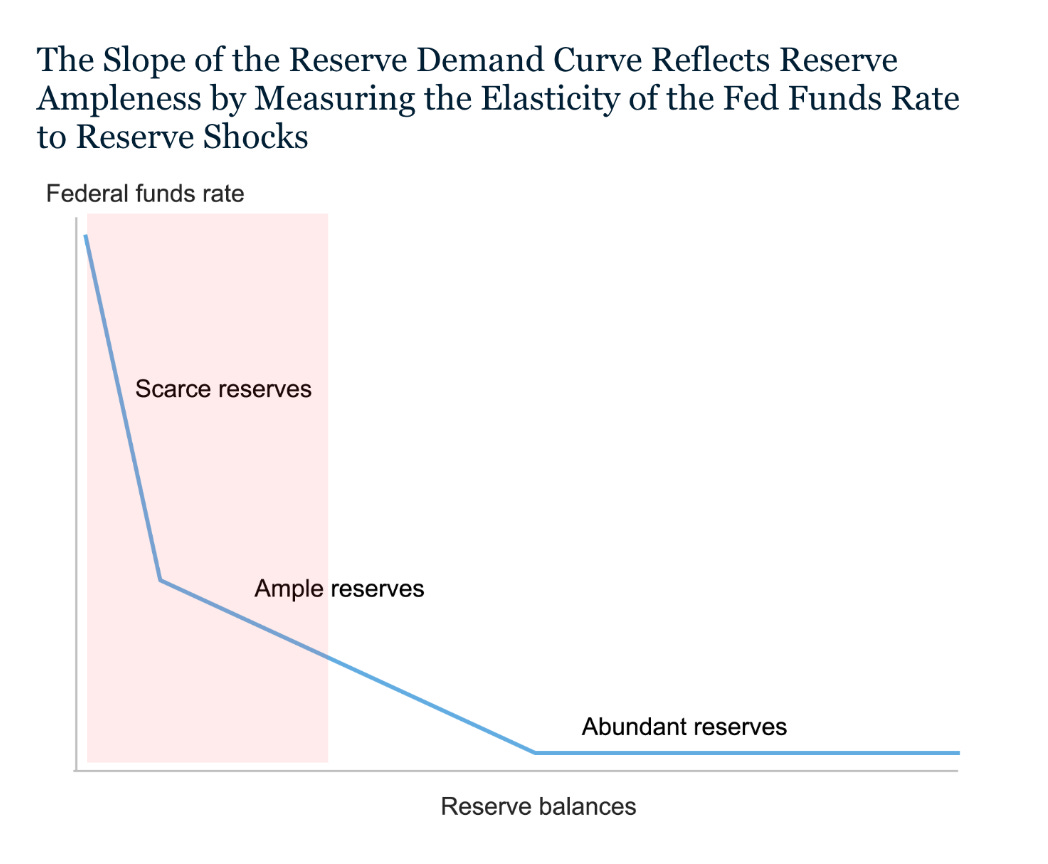

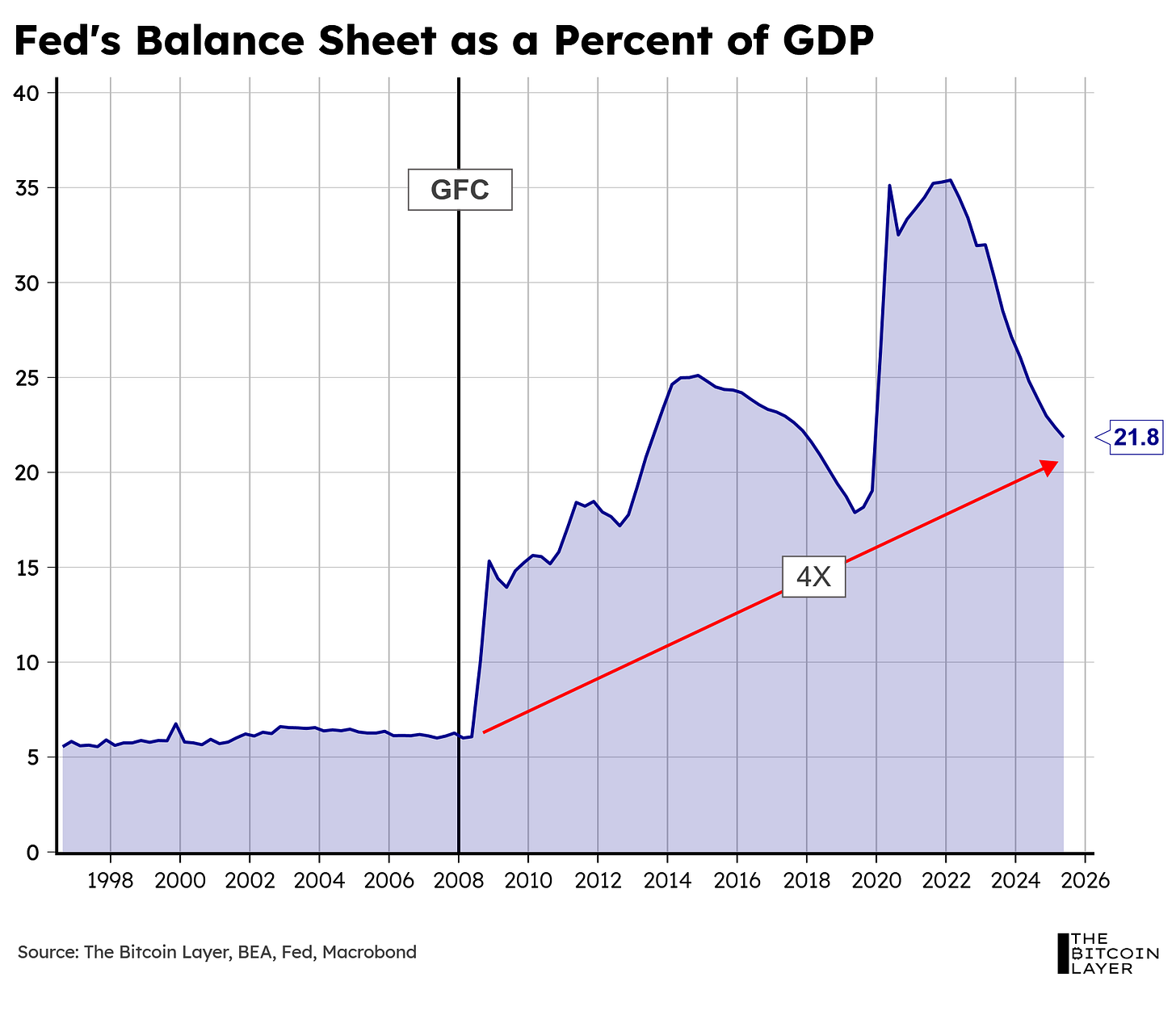

Now, remember how Alan Greenspan exploited reserves to implement the Fed’s desired target rate? Well, look at what has happened to the Fed’s balance sheet as a percent of GDP ever since the GFC (i.e., post massive liquidity injections):

So, what does that mean?

It means that reserves have moved further to the right of the reserve demand curve, where the slope is nearly zero:

Which means the Fed can no longer use the old playbook of changing reserves to change interest rates (as Alan Greenspan did). The slope here is zero, which means the Fed Funds rate does not respond to changes in the supply of reserves as much as it once did. The GFC meltdown also resulted in a disintegration of interbank trust—never again would banks look to freely lend reserves to their neighbors without collateral, thus starting a transition to a more repo-based short-term liquidity fix for banks in a pinch, wherein Treasury collateral becomes a prerequisite to accessing overnight funds.