Market Insights on Yield, QT, and Loan Forgiveness

A grasp for yield, the Fed's inability to shrink its balance sheet, and the detrimental impacts of student loan forgiveness—analysis from Nik's students.

Dear readers,

Today we bring you quick hits from some of the brilliant minds in my fixed-income class at USC Marshall this year—digestible excerpts to kick-start your morning and align your thoughts with markets and concepts. As I wrap up my fifth semester teaching rates/Fed/macro and first semester teaching bitcoin, I wanted to share some excerpts from the most thought-provoking theses I’ve come across yet. Their LinkedIn profiles will be linked too, so feel free to connect and reach out!

Grab a coffee, and let’s dive in.

Envoy is an easy Bitcoin wallet with powerful account management & privacy features.

Set it up on your phone in 60 seconds then set it, forget it, and enjoy a zen-like state of finally taking your Bitcoin off of exchanges and into your own hands.

Download it today for free on the iOS App Store or the Google Play Store.

Investors are rushing to yield, finally

The 60/40 portfolio has taken annual losses throughout history when equity risk premiums soar, but last year was the worst year for the 60/40 portfolio in history:

For many decades now, a portfolio comprised of other simple fixed-income assets and commodities has yielded roughly the same return with a vastly lower risk profile:

Shahidi’s “eBalanced” portfolio is comprised of roughly 30% Treasury Bonds, 30% TIPS, 20% equities, and 20% commodities, which since 1926 would provide an 8.1% annualized return, vs. 8.2% return from 60/40, but with a 28% greater return to risk ratio. Shahidi goes on to say that the 60/40 portfolio is 98% correlated with a 100% equity portfolio from 1929-2010.

This reality is nothing new. Non-existent yields, particularly over the last ~14 years as interest rates held near zero, have reduced the number of bonds yielding higher than the CPI inflation rate, and have led investors to divest from bonds while remaining in equities and cash, colloquially referred to as dry powder. Though, as rates have risen considerably since Fall 2021, positive real yields are finally making a comeback and investors are piling into them via many different instruments.

The Fed’s Reverse Repo Facility, a facility for UST-collateralized overnight lending for a risk-free return, has risen in use from a few billion two years ago to roughly $2 trillion:

Money market funds, where investors can park their wealth in a highly liquid pool and capture safe yield, have exploded in popularity commensurate with this rise in RRP, which is where lots of that money is parked:

And finally, rather than seeking yield in the form of a fixed-income investment like a bond or money market fund, many investors are seeking yield through 0DTE equity options. Perhaps the furthest out on the risk curve relative to other instruments, investors are piling into the closest instrument to gambling in all of finance and purchasing these options that can either yield outsized returns or expire completely worthless. 0DTE now accounts for over 45% of traded S&P 500 options:

With this colossal shift in public and private markets given the Fed’s aggressive rate hiking regime, a word of caution arises:

I hope to see the Federal Reserve take some notice of and caution to the environment in which their actions have created within public and private markets and seriously consider whether they want to be incentivizing so much “dry powder” to remain parked in these cash-like investment vehicles, like the RRP, MMFs, commercial paper, and T-bills.

Encouraging this money to remain outside of traditional public and private markets, where corporations are missing out on utilizing the capital provided for capital expenditure projects of their own, will stunt economic activity and further weigh the United States, and by extension the global economy into the ever-looming recession that we have been promised for almost a year now.

I hope to see the Federal Reserve heed these warnings and take steps to avert a global economic crisis before it is too late…

The excerpts and findings in this section were authored by Peter Martin.

The Fed simply can’t shrink its balance sheet

A major part of our framework has been the increased prominence that bank reserves have taken on since the Great Financial Crisis in 2008. It is simple to create these reserves out of thin air to imbue to banks with liquidity problems to spur economic growth—the problem comes when you try to remove them, something the Fed has yet to successfully do in any meaningful way:

The global financial crisis spawned the age of large central bank balance sheets. Any emergency, large or small, could be staved off by quantitative easing. Assets were purchased, swap lines were opened, and the Fed flexed its muscles as the global liquidity provider.

Fifteen years later, the trend prevails. In the face of a crisis, the Fed quickly steps in to provide generous, or overly generous, liquidity to the market.

However, once the Fed purchases these assets, it has great trouble eventually shedding them. The few recent times the Fed has attempted to reduce its balance sheet it has unintentionally caused some part of the market to break.

In 2013, upon Ben Bernanke’s announcement that the Fed intended to taper down the Fed’s purchase of bonds at a later date, the market went into a tailspin. Yields spiked as investors sold off their bonds in what is now known as the “taper tantrum”—an example for the ages of just how much the market has grown accustomed to the safety and solemnity that comes with the Fed as a perpetual buyer of bonds:

In 2013, it was the market’s reaction that broke the Fed’s QT; in 2019, it was a cash shortage in the repo market; in 2020, it was COVID that sealed the deal on QE4, and in 2022, it was the collapse of SVB and subsequent regional bank failures & fragility that stopped the Fed’s QT, on a net basis, in its tracks yet again:

With financial stability already on the brink after a mere fraction of the Fed’s intended work was completed, it’s safe to say that it won’t be, in our view, able to meaningfully shrink its balance sheet for much longer, if ever:

Central banks will now just have a large balance sheet. Until it causes some gargantuan problem, central bankers might not want to deal with the first, second, and third order effects of actually taking measures to shrink the Fed’s assets.

And yes, perhaps at this level, the balance sheet is sustainable and no threat to financial stability. However, what happens the next one, two, three, or four times the Fed feels compelled to pump money into the system? How will we know that the balance sheet has gotten too large? What happens in a world when Fed assets equal 50% or even 100% of GDP? The scary fact is that no one knows.

We might only find out by reaching those levels, and unearthing the consequences.

The excerpts and findings in this section were authored by Hank Rainey.

We’re excited to share our four new online class offerings:

1) Bitcoin Basics — 2) Bitcoin Valuation — 3) US Treasuries, the Fed, and Cycle Investing — 4) Introduction to Digital Assets

Sign up for these online Bitcoin & Macro Zoom Classes at thebitcoinlayer.com/learn

Student loan forgiveness is nothing but a moral hazard machine

The cost of higher education in the United States has increased in eyewatering fashion over the past few decades. By guaranteeing loans to everybody, the cost of tuition inevitably rises, which forces even more people to borrow—rinse and repeat. This vicious feedback loop of awful loan origination standards saddles those that take it on with oft unserviceable debt:

Pell Grants, which once covered almost 80 percent of the cost of a four-year public college degree for students from working families, now only cover a third. As a result, the average undergraduate student now graduates with nearly $25,000 in debt, according to the Department of Education.

Proponents have come out of the woodwork over the years for student loan forgiveness. Moral hazard is already at nuclear levels, and the decision by our policymakers is for yet more easy credit, thus moral hazard. Genius.

The economic implications of student loan forgiveness are as follows:

A. Impact on the federal budget deficit

Although canceling student debt would alleviate the financial hardships facing millions of Americans, it would also significantly cost the federal government in forgone loan principal and interest payments…

Forgiving $10,000 per borrower in student debt would cost roughly $250 billion, while forgiving $50,000 per borrower would cost $950 billion.

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that forgiving all student loans would increase the deficit by $1.36 trillion over ten years.

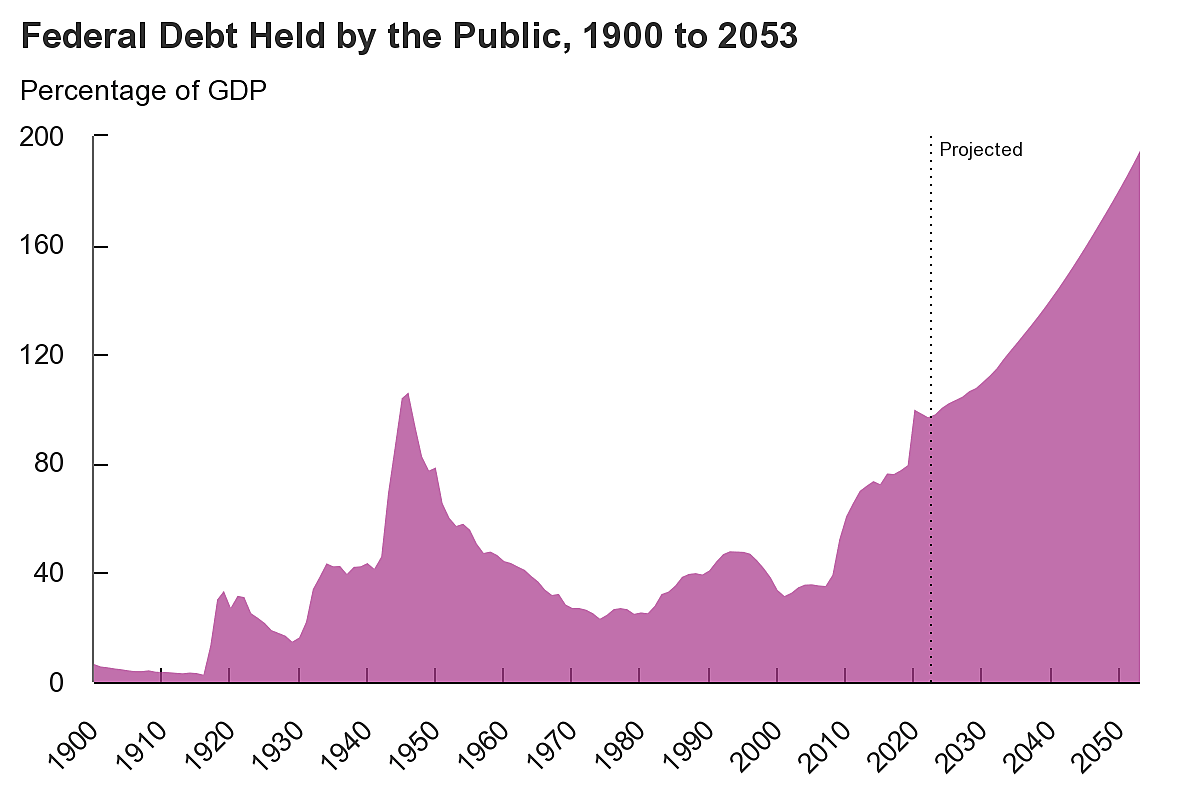

The idea is to shift evermore of the public debt burden out into the future and onto the next generation—the percentage of Federal debt held by the public is projected to rise from roughly 100% today to 200% by 2053:

Not to mention the cost borne by the American taxpayer. Two options to reduce such a crazy deficit incurred with student loan forgiveness are to decrease spending elsewhere or raise taxes—can you guess which one US policymakers will likely choose if given the option? Hint: the one with less work involved:

To exemplify the opportunity cost of student loan forgiveness, we can look at the ‘COVID-19 Emergency Relief and Federal Student Aid’ pause established by President Trump (and continued by President Biden) which provisionally paused all student loan payments during the COVID-19 epidemic.

This payment pause is estimated to cost taxpayers roughly $5 billion per month ($60 billion per year) as reported by the Wall Street Journal in an article in 2021.

Extrapolating the outcomes of student loan forgiveness, it will not be stimulative to the economy as these debt burdens are lifted off of the shoulders of students, because the cost will still have to be borne by the public indirectly, and over many years:

The CRFB also stated that student debt cancellation would be an ineffective form of stimulus, providing a small boost to the near-term economy relative to the cost. Student debt cancellation will increase cash flow by only $90 billion per year, at a cost of $1.5 trillion.

Economists further argue that the majority of the funds would go towards paying off existing debts rather than stimulating new economic activity and would provide minimal stimulus, while some even argue it would shrink the economy.

Eliminating the need for students to repay student loans will distort credit incentives even further for future borrowers. If you set this precedent, people will knowingly take on debt that they cannot repay with the expectation that they won’t have to.

Allowing bad, unserviceable debt to proliferate throughout the system will be catastrophic for lenders when the day comes that these students default—for the sake of maintaining some level of financial stability in the student loan market, it must be avoided.

The excerpts and findings in this section were authored by Renu Mulay.

And that’s it! We hope you enjoyed a break in the action to take in some of the valuable insights provided by some of the next generation’s best market minds.

Until next time,

Nik & Joe

Bitcoin's most intuitive hardware wallet just got cheaper.

Passport is now just $199. Set it up in minutes, take your bitcoin off of exchanges with ease, and experience unmatched peace of mind.

Get it at thebitcoinlayer.com/foundation & receive $10 off with code BITCOINLAYER

Your students appear to have more common sense, and rational thinking abilities, than the current administration and Fed researchers combined. Great that they can explore these important issues