Profound implications of Saylor's latest revelation

Explaining the significance of Michael Saylor's latest interview with The Bitcoin Layer.

Dear readers,

Do you ever get the feeling that something is wrong, but you just can’t articulate it? Whether or not you lived through more idyllic times, our current society can feel upside down. Debt is encouraged, and inflation eats away at our purchasing power. As long-time participants in bitcoin as an asset class, technology, and learning gateway, we are aware of the central banking and commercial banking monetary layers and their limitless bounds, but even we were blown away at the corporate finance revelation described by Michael Saylor and what it could mean for our world. It demanded a follow-up for our subscribers.

River is the Bitcoin exchange of choice for the long-term investor.

Securely buy Bitcoin at the tightest spreads in the industry, have peace of mind thanks to their 100% full-reserve cold storage custody, and enjoy zero fees on recurring orders. Need help? They have US-based phone support for all clients.

Invest in Bitcoin with confidence at River.com/TBL

Corporate Finance 101

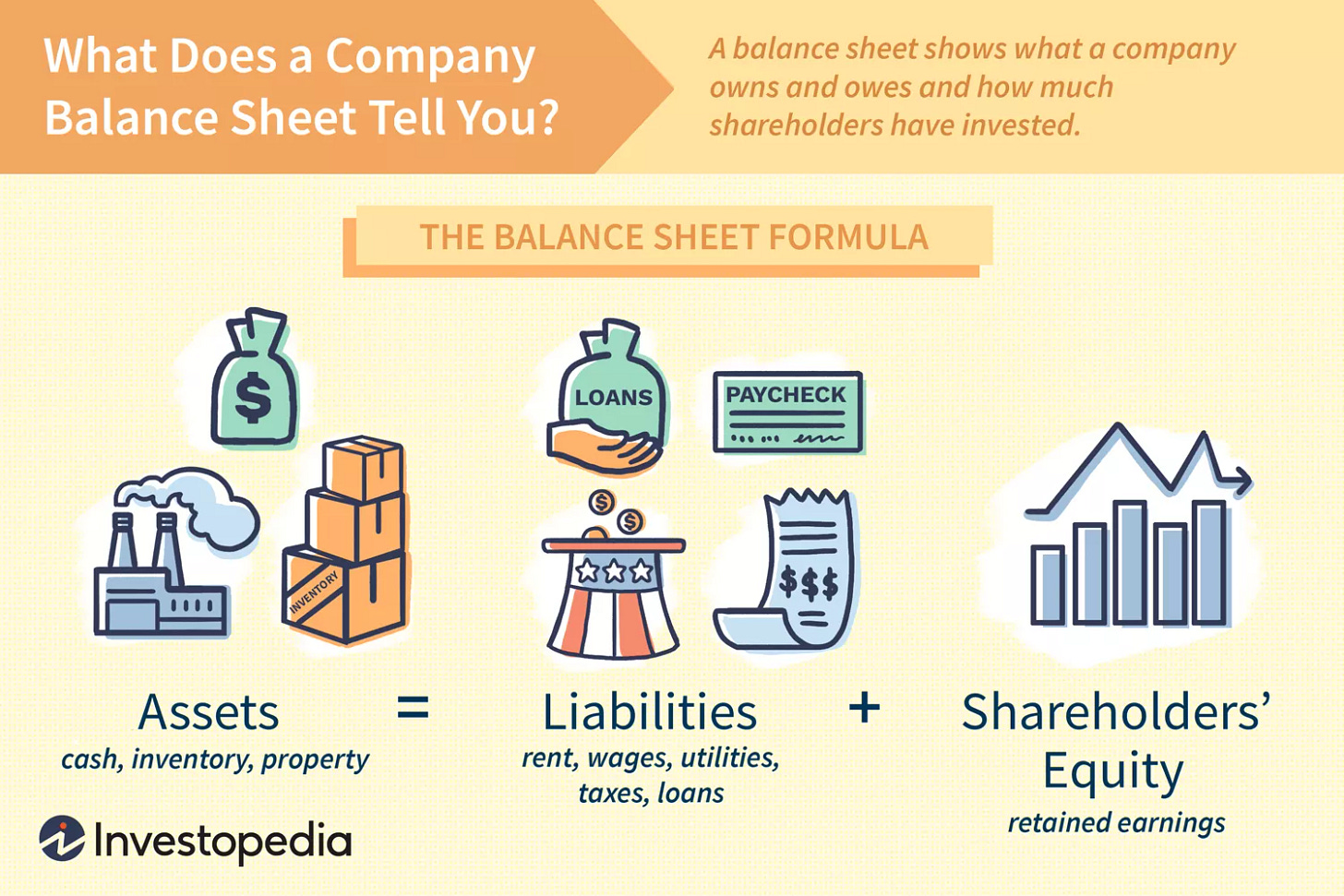

Before we dive into Saylor’s theory, let’s begin with a setup of corporate finance and the basics of balance sheet mechanics:

There are three sections of a balance sheet—the assets, which are funded by equity and liabilities. Assets for a corporation mostly have to do with the projects that generate cash flow, such as buildings, equipment, and intellectual property. A company’s equity is its starting capital, or cash it has raised that it doesn’t have to pay back (aside from dividends, which we’ll discuss). A company’s liabilities are its debt—any capital it has raised that does require repayment.

Now, with these three sections explained, what does a company do? It uses equity and debt sources of capital to fund projects in order to generate cash flow.

That is the simplest way to describe the mechanics of a corporate balance sheet. Now, if the company is trying to make as much money as it can, does it make sense that it’ll try to fund as many cash-generating projects as possible? Yes, and in order to do that, companies must expand their balance sheet.

How, one might ask, is the company best positioned to do this? It can raise equity, or it can issue debt (borrow via loans or by accessing the bond market).

In the first tenet of Saylor’s argument, he outlines how the basic return hurdle for equity capital is at least 7%—this is because the monetary system expands by about that much when measured over the past several decades. Even though CPI fluctuates wildly, measuring monetary expansion over a longer time horizon gives him the confidence to go into structuring his thesis with this 7% required rate of return.

If equity holders are going to invest in companies, Saylor is suggesting that they are going to require a rate of return much higher than 7%. But in order to do this, companies cannot simply generate cash flow and invest that directly into Treasury bills. Even with today’s 5% yield, equity returns of 10% cannot be achieved simply by holding cash-like instruments once profits have been generated. Shareholders trust management to take profits and reinvest them.

What are the options for a company to reinvest profits, and how does he work bitcoin into this general theory of capital allocation by treasurers of corporations?