The LIBOR ⟶ SOFR transition cements the Fed's global monetary authority

A victory for the Fed, and a relegation for European banks.

Dear readers,

One of the world’s most widely used reference rates is close to being completely phased out in favor of a new secured rate that falls partly under the umbrella of the Federal Reserve. In the wake of the Great Financial Crisis, interbank lending, which was once presumed to be essentially risk-free, became widely understood as inundated with potential risks that could threaten the solvency of interconnected creditors overnight. Banks suddenly became increasingly wary of lending to one another, threatening to grind the world’s capital and money markets to a halt if a solution wasn’t found.

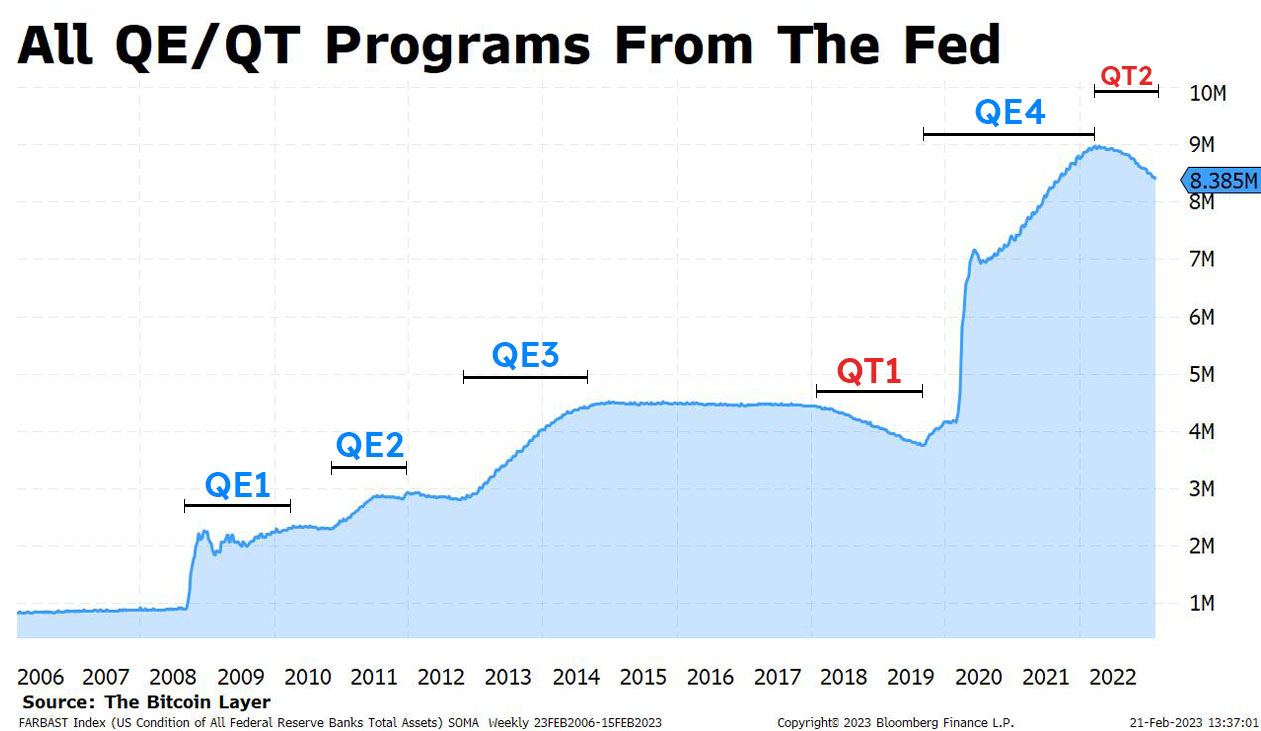

The band-aid solution came in the form of Quantitative Easing programs from the Fed, and the long-term solution—the total transition from unsecured to secured funding rates—is at our doorstep. With this change, the Fed will enter a new echelon of dominance never before seen in global financial markets.

Check out our friend Concoda’s piece on the LIBOR → SOFR transition here.

Collusion and corruption shouldn’t set the cost of capital

LIBOR, which stands for London Interbank Offered Rate, is a benchmark short rate published daily by the Intercontinental Exchange (ICE). Major global banks are asked the rate they would charge other banks for short-term funding loans—those rates are then averaged into the published LIBOR rate. The most widely quoted LIBOR rate is the 3-month US dollar loan rate, which is commonly simply referred to as its namesake, LIBOR.

This interbank lending rate has underpinned dollar financial markets since its introduction in 1986—serving as the benchmark interest rate for writing business loans, consumer loans, mortgages, car loans, and for pricing financial assets such as derivatives. Following its introduction, derivatives started referencing LIBOR, such as Forward Rate Agreements and Overnight Index Swaps (OIS)—today, these derivatives accommodate billions of dollars worth of daily trade volume and have become critical cogs for hedging in the global financial system.

Since it’s fully unsecured, LIBOR is very sensitive to fluctuations in the credit cycle. With no collateral, the rate is determined by the creditworthiness of the banks being lent to, making it particularly susceptible to skyrocketing during credit events. This was the case during the Great Financial Crisis when it rose dramatically, and its spread relative to OIS (this time, referencing Fed Funds) widened to extreme levels as banks stopped dealing with one another:

As the GFC unfolded, undesirable aspects of LIBOR as a proxy for real interbank loan rates started to emerge. Since the rate was fashioned based on the submissions from a panel of member banks, many of whom were being dishonest in order to project strength in the wake of the financial crisis, it quickly became apparent that LIBOR was being manipulated to the point that it was no longer viable as a deeply entrenched reference rate. Reporting banks would deliberately underreport the rates they were being charged by other banks for loans to make themselves seem more creditworthy. This collusion between banks to underreport their rates so they could borrow more cheaply when that day’s LIBOR was published, while also colluding with swaps traders to provide rates that would benefit them, perfectly sums up the level of backroom shadiness that made LIBOR a reference rate open to extreme corruption.

Deceiving fellow banks and the investing public by underplaying the level of associated risk with a given investment was the target of legislative reform following the GFC, so it’s no wonder that LIBOR would be phased out after these holes were discovered. The price of lending to another bank on an unsecured basis could no longer be accurately reported—banks instead started relying on collateralized lending with quality assets. It wasn’t long before the discussion began to search for a secured alternative to unsecured LIBOR.

The birth of SOFR

Amidst the desire for safer interbank lending, the Fed strategically found itself at the center of reconstructing a new, secured reference rate. Using its status as the world’s most trusted monetary authority, the Federal Reserve began publishing SOFR, or the Secured Overnight Financing Rate, on April 2nd, 2018. SOFR is created by annualizing the average overnight rate offered in the Treasury repurchase (repo) market, whereby short-term cash loans are made against US Treasury collateral.

For a more comprehensive history of LIBOR, Treasury repo, and the Great Financial Crisis, read (or listen to) Nik’s book, Layered Money.

A benchmark rate based on observable transactions in the Treasury repo market is superior to self-reported interbank loan rates under the LIBOR standard which were susceptible to regular manipulation. This makes SOFR more worthy of the proverbial ‘risk-free rate’ moniker. The Treasury repo market is also much more liquid than the interbank loan market at a staggering $21 trillion in size, with over $1 trillion in daily trade flows.

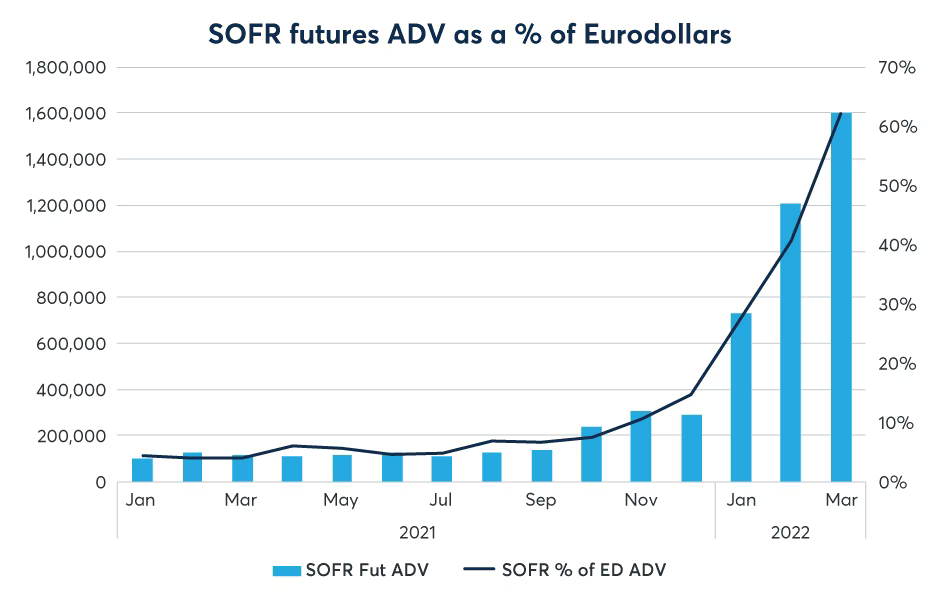

As the years have progressed since the start of its rollout, SOFR is finally turning the corner as the most widely utilized reference rate. This is observable with SOFR futures and options adoption going parabolic at the beginning of 2022:

Take a look at SOFR futures relative to Eurodollar futures—they are steadily gaining on the king of dollar rate futures contracts in terms of average daily volume:

The creation of the standing repo facility and interest on reserve balances (IORB) in July 2021, and the creation of the reverse repo facility (ON RRP) in 2013 were the Fed’s foray into the Treasury repo market. Both of these facilities have normalized UST-collateralized lending at a rate set by the Federal Reserve over the last two decades, cementing the Fed’s authority over short-term interest rates. SOFR is the Fed’s latest iteration of this same policy tool: exert influence over short rates by staying readily involved in US dollar funding markets.

Why does SOFR give more power to the Fed if the rate is set by the rates offered in the Treasury repo market? The Federal Reserve not only is one side of a substantial portion of UST repo transactions via its standing repo facility, but it also has a great deal of influence over the availability of US Treasuries via its reverse repo facility and its on-again, off-again quantitative easing and tightening programs. The size and status of the Fed as the least risky financial counterparty see it dominate the $3 trillion in daily US dollar repo volumes. The Fed’s repo policy rates on either side of the SOFR rate and its heavy involvement in each market mean that the Fed essentially sets SOFR.

SOFR expands the Fed’s power

As the SOFR transition continues, the Fed claws back control from the realm of LIBOR and the Eurodollar system. The Fed operates under an ample reserves framework—a system by which the Fed maintains a certain level of bank reserves in the financial system to effectively exert control over short-term interest rates and administer its own set of policy rates. Through ample reserves and the Fed’s repo window & SOFR construct, European banks pose less of a threat to the global financial system than they did 10 and 20 years ago—frankly, an astounding victory from the American financial system’s perspective.

The Fed will continue double tightening, a wind down of its balance sheet while increasing SOFR. Either form has the potential to cause mass destruction; rolling over debt at higher rates and ample reserves that suddenly un-ample themselves are each a net negative on consumption and liquidity. The breaking point exists, but its location elusive.

LIBOR has already been largely phased out in favor of SOFR as the benchmark rate used by most financial institutions, but there are a few nails yet to be hammered in before the coffin is shut. CME Eurodollar futures contracts are transitioning to SOFR on April 14th, and US dollar LIBOR is cold turkey ceasing publication after June 30th. This is a meteoric transition for world dollar markets.

The ON RRP rate sets a floor under overnight rates, IORB motivates banks to hold an ample amount of their liquidity at the Fed, and SOFR underpins US dollar credit markets—all are controlled by the Federal Reserve. When tracking the history of European banks and their outsized impact on the dollar system’s evolution, this SOFR transition can only be described as a seismic shift.

Until next time,

Nik & Joe

The Bitcoin Layer does not provide investment advice.